Place value: What’s in a number?

View Sequence overviewNumbers can be sorted and classified using their properties.

The position of a digit in a number gives it value.

Whole class

What’s in a number? PowerPoint

3 hoops (different colours if possible)

3 A4 sheets of paper

Texta

Each group

Task 2 Number cards to sort Student sheet

One of the following:

- Scissors and glue (to cut out and stick number cards)

- Sticky notes & pencil (to copy each number onto a sticky note)

A3 sheet of paper

Glue

Task

Revise: In the last task we sorted numbers into groups by noticing how they were similar and different.

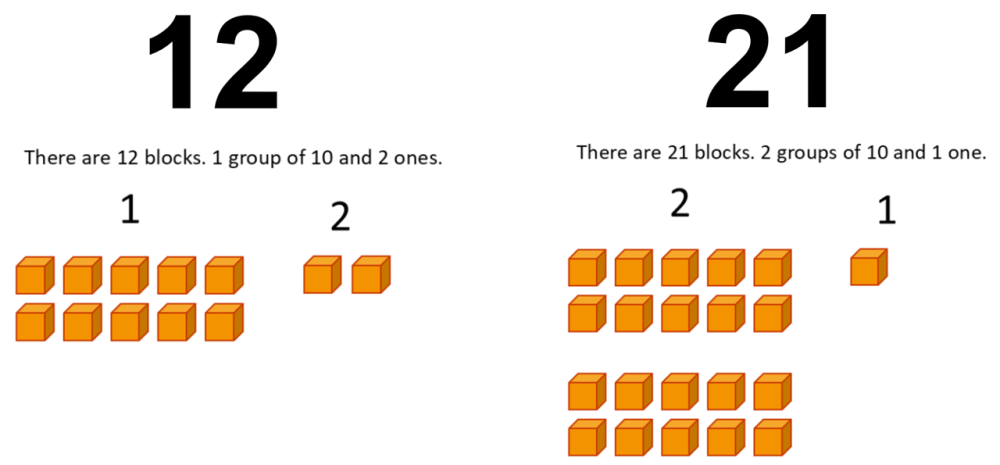

Show slide 6 of What’s in a number? PowerPoint which displays the numbers 12 and 21.

Discuss:

- What do you notice about these numbers?

- How are the numbers the same?

- How are they different?

- What happens when the digits 1 and 2 swap places in the number?

Ask students to discuss examples of numbers where the same digits in different positions make different numbers, and to share their reasoning and understanding of this.

Show slide 7 and discuss how we can represent and model 12 and 21.

Show slide 8 and explain that students will be sorting these numbers.

Pose the task: Sort these numbers into groups. Then sort them into groups in a different way.

The place, or position, of a number gives its value

Place value is a powerful mathematical idea that underpins our base-ten number system.

The Launch phase of this task focuses students’ attention on place value, highlighting that the position of a digit determines its value within a number. In this task, students work with one-, two- and three-digit numbers, which use the place values of ones, tens, and hundreds.

Each digit in a number indicates how many units of that place value are present, and the sum of these units makes the whole number. For example, although the digits in 12 and 21 are the same, their positions change their values, resulting in different totals. Students recognise that both the size of the unit and number of units are needed to describe the quantity represented. They recognise that the digit 2 in 12 represents a different value to the 2 in 21 because the 2s are in different positions, and that the 2 in 21 represents a value of 20 because it represents 2 groups of 10.

Using pop-stick bundles to model numbers supports students in visualising the magnitude of each place. In 12, one bundle of ten pop sticks and two single pop sticks show that:

10 + 2 = 12 or 1 ten + 2 ones = 12

When the digits are rearranged to form 21, the same modelling process shows the change in value explicitly:

20 + 1 = 21 or 2 tens + 1 one = 21

Over time, students develop trust in the base-ten structure—that 10 ones make 1 ten, and 10 tens make 1 hundred. This understanding is strengthened through repeated experiences with a range of representations (concrete, pictorial, and symbolic) that consistently embody these relationships.

Place value is a powerful mathematical idea that underpins our base-ten number system.

The Launch phase of this task focuses students’ attention on place value, highlighting that the position of a digit determines its value within a number. In this task, students work with one-, two- and three-digit numbers, which use the place values of ones, tens, and hundreds.

Each digit in a number indicates how many units of that place value are present, and the sum of these units makes the whole number. For example, although the digits in 12 and 21 are the same, their positions change their values, resulting in different totals. Students recognise that both the size of the unit and number of units are needed to describe the quantity represented. They recognise that the digit 2 in 12 represents a different value to the 2 in 21 because the 2s are in different positions, and that the 2 in 21 represents a value of 20 because it represents 2 groups of 10.

Using pop-stick bundles to model numbers supports students in visualising the magnitude of each place. In 12, one bundle of ten pop sticks and two single pop sticks show that:

10 + 2 = 12 or 1 ten + 2 ones = 12

When the digits are rearranged to form 21, the same modelling process shows the change in value explicitly:

20 + 1 = 21 or 2 tens + 1 one = 21

Over time, students develop trust in the base-ten structure—that 10 ones make 1 ten, and 10 tens make 1 hundred. This understanding is strengthened through repeated experiences with a range of representations (concrete, pictorial, and symbolic) that consistently embody these relationships.

Connecting representations

Different representations enhance sense-making by helping students build meaning, see connections, and reason about mathematics, rather than simply manipulating numbers or symbols. When representations are intentionally linked, students develop deeper, more durable understanding.

The PowerPoint slides 6 and 7 used during the Launch phase of this task make explicit links between digits and the place they occupy in a number. Students may already be familiar with the idea that two-digit numbers are composed of tens and leftover ones, and they may recognise that swapping the digits in the number 12 creates the number 21. However, some students may not yet extend their thinking to understand what this change means in terms of value or quantity. Simply rearranging digits does not capture how the value of each digit changes according to its position.

Using concrete materials alongside the digits helps to model this change in value and emphasises that a digit always represents how many of a particular unit. For example, the number 12 consists of 1 unit of ten and 2 units of one, whereas 21 consists of 2 units of ten and 1 unit of one. The model therefore represents not only the change in the digits’ positions but also the change in the unit and value each digit represents.

Different representations enhance sense-making by helping students build meaning, see connections, and reason about mathematics, rather than simply manipulating numbers or symbols. When representations are intentionally linked, students develop deeper, more durable understanding.

The PowerPoint slides 6 and 7 used during the Launch phase of this task make explicit links between digits and the place they occupy in a number. Students may already be familiar with the idea that two-digit numbers are composed of tens and leftover ones, and they may recognise that swapping the digits in the number 12 creates the number 21. However, some students may not yet extend their thinking to understand what this change means in terms of value or quantity. Simply rearranging digits does not capture how the value of each digit changes according to its position.

Using concrete materials alongside the digits helps to model this change in value and emphasises that a digit always represents how many of a particular unit. For example, the number 12 consists of 1 unit of ten and 2 units of one, whereas 21 consists of 2 units of ten and 1 unit of one. The model therefore represents not only the change in the digits’ positions but also the change in the unit and value each digit represents.

Divide students into pairs to work together and provide each pair with Task 2 Number cards to sort Student sheet, A3 paper and either scissors (for cutting out the number cards) or pencils and sticky notes (for copying out the numbers).

Allow students time to prepare (cut out/copy) the numbers to make a set of number cards and to sort their numbers into groups in different ways. Ask them to record how they sorted these numbers by drawing a picture of each different sort and labelling the categories/groups.

- Do students use place value or face value (the value of each individual digit) to sort?

- Do they sort into more than two groups?

- Do they label categories to include every number card in their sort?

Spotlight: Highlight student work that demonstrates sorting numbers, including examples of:

- using place value.

- labelling each category.

- using all/most numbers.

- sorting into more than two groups.

- sorting that includes a misconception.

Ask:

- What do you already know that helped you begin?

- What prior knowledge do students access?

- How did you decide to sort all/most numbers into these groups?

- Do students recognise that digit position is important to a number’s value?

- Can you explain this part a bit more? (point to a section needing clarification)

- What is another way to sort these numbers?

Allow students time to refine and make changes to how they have sorted the numbers, if they choose.

Ask students to choose their favourite way of sorting the numbers and record this by sticking the groups of sorted numbers onto paper. They may draw around the different groups to make them clear and label the criteria that they used to sort the numbers.

Select student work demonstrating number sorts which show clear place value properties to share and discuss during the Connect phase.

Spotlight

A spotlight is used here to pause student work and to share examples of how students are sorting numbers into categories based on similarities they notice. Rather than telling students exactly what to do, the teacher uses these examples to help guide and extend the class’s thinking.

During the spotlight, students are encouraged to look at the examples and compare them with their own work. The teacher highlights student work that:

- notices similarities and differences between numbers, such as:

- the number of digits.

- how a digit’s value changes when it moves to a different position.

- uses clear labels so each category is easy to understand.

Including an example that isn’t quite right can be especially helpful during a spotlight. This gives students the chance to talk about what doesn’t work, explain their thinking, and discuss what would need to change to make it correct.

After the spotlight, students have time to go back to their own work and make changes if they choose, using ideas they found helpful from the examples they’ve seen.

A spotlight is used here to pause student work and to share examples of how students are sorting numbers into categories based on similarities they notice. Rather than telling students exactly what to do, the teacher uses these examples to help guide and extend the class’s thinking.

During the spotlight, students are encouraged to look at the examples and compare them with their own work. The teacher highlights student work that:

- notices similarities and differences between numbers, such as:

- the number of digits.

- how a digit’s value changes when it moves to a different position.

- uses clear labels so each category is easy to understand.

Including an example that isn’t quite right can be especially helpful during a spotlight. This gives students the chance to talk about what doesn’t work, explain their thinking, and discuss what would need to change to make it correct.

After the spotlight, students have time to go back to their own work and make changes if they choose, using ideas they found helpful from the examples they’ve seen.

The purpose of this Connect phase is for students to understand that:

|

Bring the class together to sit in a circle on the floor. Invite selected students to describe and explain how they sorted the numbers and to justify their choice of categories/labels.

Discuss:

- Why did you sort the numbers in this way?

- Why are numbers with the same digit in different groups?

- Discuss what students notice about the same digit in different numbers and its value because of its position in the number. For example, 4 has a value of 40 or 4 tens in 40, 140, and 42, but has a value of 4 in 34.

- Were there any numbers which did not belong in any groups? Why did they not belong in a group?

- Did any numbers belong in more than one group? Why do they belong in more than one group?

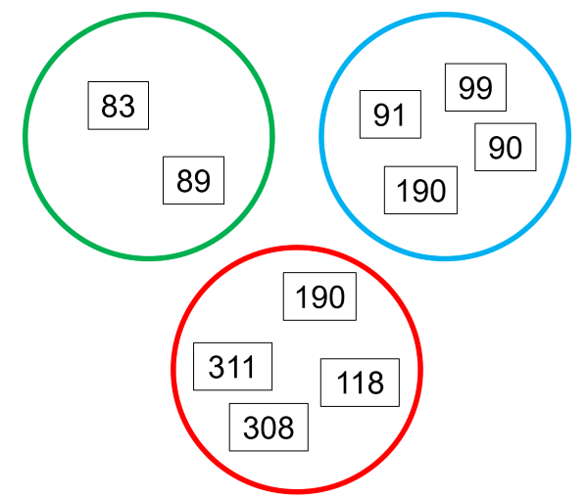

Arrange 3 hoops where they are visible to the whole class and sort the Number cards into the corresponding hoops as in the below image.

Explain that the hoops represent a Venn diagram, a useful model that mathematicians draw to sort and categorise things.

Ponder: I wonder how these numbers have been sorted.

Invite students to turn and talk to the student next to them and discuss how they think the numbers have been sorted. Prompt student thinking as they engage in turn and talk:

- What do you notice that is similar about the numbers in a circle?

- What do you notice that is different about the numbers in other circles?

Invite students to explain how the numbers have been sorted. They should notice the numbers have been sorted based on the number of tens:

- Green circle: 8 tens or eighty

- Blue circle: 9 tens or ninety

- Red circle: Over one hundred (or more than 10 tens)

- Students may struggle to explain the idea that there are more than 10 tens in the red group.

Label each circle with these criteria and discuss:

- How can we explain this in another way?

- How many tens altogether in this number?

- Can you think of another way to sort them?

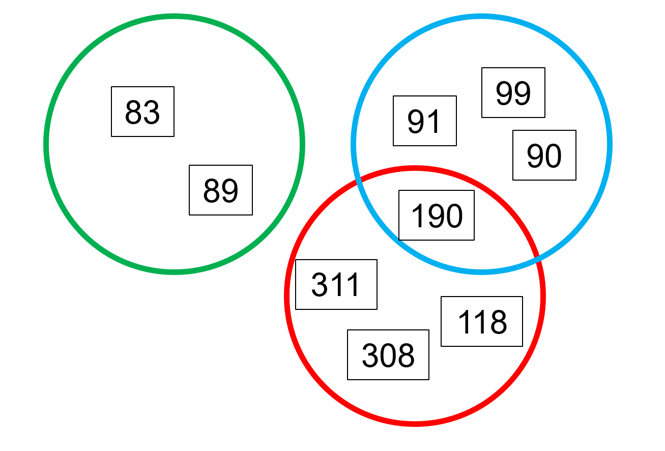

- Do you notice any numbers that fit in more than one circle?

Students may notice that 190 belongs in two groups—ask them to explain why they think it belongs in both.

Ponder: I wonder how we could show that 190 belongs in both groups.

Invite student suggestions and orchestrate the overlapping of the hoops to put 190 in the intersection of the red and blue hoops:

Invite students to describe how 190 fits in this overlap. This is again an opportunity to revoice student responses, using correct terminology, distinguishing between digit and value.

Renaming

Making connections between the position of the digits in a number, and what this means for the value of each digit, is a powerful mathematical idea for students. To make sense of this idea, it is useful to draw students’ attention to what the position of each digit is communicating. Focusing on students’ prior concrete experiences with renaming can be one way of achieving this.

Students should already have had many experiences of partitioning numbers to develop the understanding that all numbers are made up of smaller parts. This part-part-whole understanding of number underpins the idea that numbers greater than 10 can be made of units of ten and units of one. This is then expanded to include units of a hundred. For example, the number 62 can be renamed as 6 tens and 2 ones, while the number 162 can be renamed as 1 hundred, 6 tens and 2 ones. Both of these examples use standard partitioning to match each digit to its place value part.

Note here that the numbers 62 and 162 have not been recorded as 60 + 2, or 100 + 600 + 2. They are recorded as a count of place value units, which emphasises the multiplicative nature of our base-ten number system. This reduces cognitive load for students by encouraging students to consider 1 of one unit, 6 of another unit, and 2 of another (Siemon et al., 2011, p. 305).

In this task, students are also encouraged to consider 3-digit numbers as having more than 10 tens, which introduces the idea of non-standard partitioning where 1 hundred is renamed as 10 tens. For example, 162 can be renamed as 16 tens and 2 ones, or 15 tens and 12 ones and so on.

This is one of the most difficult aspects of place value for students to understand. Therefore, they need to have had extensive experiences of building 1 ten from 10 ones, and 1 hundred from 10 tens, using concrete representations to explore the idea that when we rename any number, however we choose to regroup the number, its value remains the same.

To clarify these ideas with your students, you may find it helpful to model numbers using concrete materials to show how a quantity may be physically regrouped to reflect how it has been renamed.

References

Siemon, D., Beswick, K., Brady, K., Clark, J., Faragher, R., & Warren, E. (2011). Teaching mathematics: Foundations to middle years. Oxford University Press.

Making connections between the position of the digits in a number, and what this means for the value of each digit, is a powerful mathematical idea for students. To make sense of this idea, it is useful to draw students’ attention to what the position of each digit is communicating. Focusing on students’ prior concrete experiences with renaming can be one way of achieving this.

Students should already have had many experiences of partitioning numbers to develop the understanding that all numbers are made up of smaller parts. This part-part-whole understanding of number underpins the idea that numbers greater than 10 can be made of units of ten and units of one. This is then expanded to include units of a hundred. For example, the number 62 can be renamed as 6 tens and 2 ones, while the number 162 can be renamed as 1 hundred, 6 tens and 2 ones. Both of these examples use standard partitioning to match each digit to its place value part.

Note here that the numbers 62 and 162 have not been recorded as 60 + 2, or 100 + 600 + 2. They are recorded as a count of place value units, which emphasises the multiplicative nature of our base-ten number system. This reduces cognitive load for students by encouraging students to consider 1 of one unit, 6 of another unit, and 2 of another (Siemon et al., 2011, p. 305).

In this task, students are also encouraged to consider 3-digit numbers as having more than 10 tens, which introduces the idea of non-standard partitioning where 1 hundred is renamed as 10 tens. For example, 162 can be renamed as 16 tens and 2 ones, or 15 tens and 12 ones and so on.

This is one of the most difficult aspects of place value for students to understand. Therefore, they need to have had extensive experiences of building 1 ten from 10 ones, and 1 hundred from 10 tens, using concrete representations to explore the idea that when we rename any number, however we choose to regroup the number, its value remains the same.

To clarify these ideas with your students, you may find it helpful to model numbers using concrete materials to show how a quantity may be physically regrouped to reflect how it has been renamed.

References

Siemon, D., Beswick, K., Brady, K., Clark, J., Faragher, R., & Warren, E. (2011). Teaching mathematics: Foundations to middle years. Oxford University Press.

Turn and talk

Talk moves contribute to a positive classroom climate, with students developing the communication skills to articulate how they think about important mathematical ideas. Talk moves are “simple conversational actions that have the potential to make discussions productive” (Chapin & O’Connor, 2007, 119).

‘Turn and talk’ has been used in this task to support students as they develop as a community of learners, empowered to share their mathematical thinking. Using pedagogical strategies such as turn and talk allows noticings to be shared in small groups or pairs so that thinking can be articulated, clarified and perhaps even academically challenged in a safe space before sharing with the whole group.

References

Chapin, S & O’Connor, C (2007). Academically Productive Talk: Supporting Student Learning in Mathematics, in Martin, W.G., Strutchens, M. & Elliott, P. (eds.), The Learning of Mathematics, 69th NCTM Yearbook, National Council of Teachers of Mathematics: Reston, VA, pp. 113-128.

Talk moves contribute to a positive classroom climate, with students developing the communication skills to articulate how they think about important mathematical ideas. Talk moves are “simple conversational actions that have the potential to make discussions productive” (Chapin & O’Connor, 2007, 119).

‘Turn and talk’ has been used in this task to support students as they develop as a community of learners, empowered to share their mathematical thinking. Using pedagogical strategies such as turn and talk allows noticings to be shared in small groups or pairs so that thinking can be articulated, clarified and perhaps even academically challenged in a safe space before sharing with the whole group.

References

Chapin, S & O’Connor, C (2007). Academically Productive Talk: Supporting Student Learning in Mathematics, in Martin, W.G., Strutchens, M. & Elliott, P. (eds.), The Learning of Mathematics, 69th NCTM Yearbook, National Council of Teachers of Mathematics: Reston, VA, pp. 113-128.

Discuss how digits have different values because of their position in a number and that a digit, such as ‘1’ can be worth 1 one, 1 ten or 1 hundred depending on where it is in a number.

Explain: The place of a digit in a number gives its value and when a digit moves places, its value changes.

You may choose to use concrete materials (such as pop sticks, ten frames, or unifix cubes) to model some of the numbers on the cards in the same way as slides 6 and 7 on the PowerPoint—using materials to represent the concrete quantity alongside the number. This helps students see that although the digits change places, the materials cannot simply be swapped because they represent different unit values. For example, 24 and 42 use the same digits but represent different units.